I sit-down with Dr. Nina Kraus of Northwestern University to talk about all things sound, especially her recent book, “Of Sound Mind” from MIT Press. I reached out to Dr. Kraus because of an article excerpted from her book within which she talks about her ongoing research into “drone compositions.”

In the first part of the interview, we covered Part I of “Of Sound Mind” and began covering Part II. In this second part of the interview, we’ll finish covering Part II then wade-out beyond the breakers to discuss Dr. Kraus’ ongoing research interests and our mutual love of drone-y sounds and music, the latter most relevant to the ÆTERNUM project.

The transcription was done with a little service called Sonix.AI, which allows you to do audio transcription on an hourly rate. Very convenient for small-timers like me. If you want to use their service, please use this link so I can get credit for it: https://sonix.ai/invite/ovywbwe.

“Our Sonic Selves,” continued…

Friar Z: [00:00:00] You know, I did find fascinating the section on birdsong and the differences in similarities with human beings. And I had read about a year ago a work by Berwick and Chomsky that was titled "Why Only Us?" when it comes to language, and they also look at songbirds in their own research. So, this really seems to be an exceptional area of where we can look at musicality, rhythm, and that sort of thing in other species and do a comparison and contrast. Could you speak about that a little bit from your book?

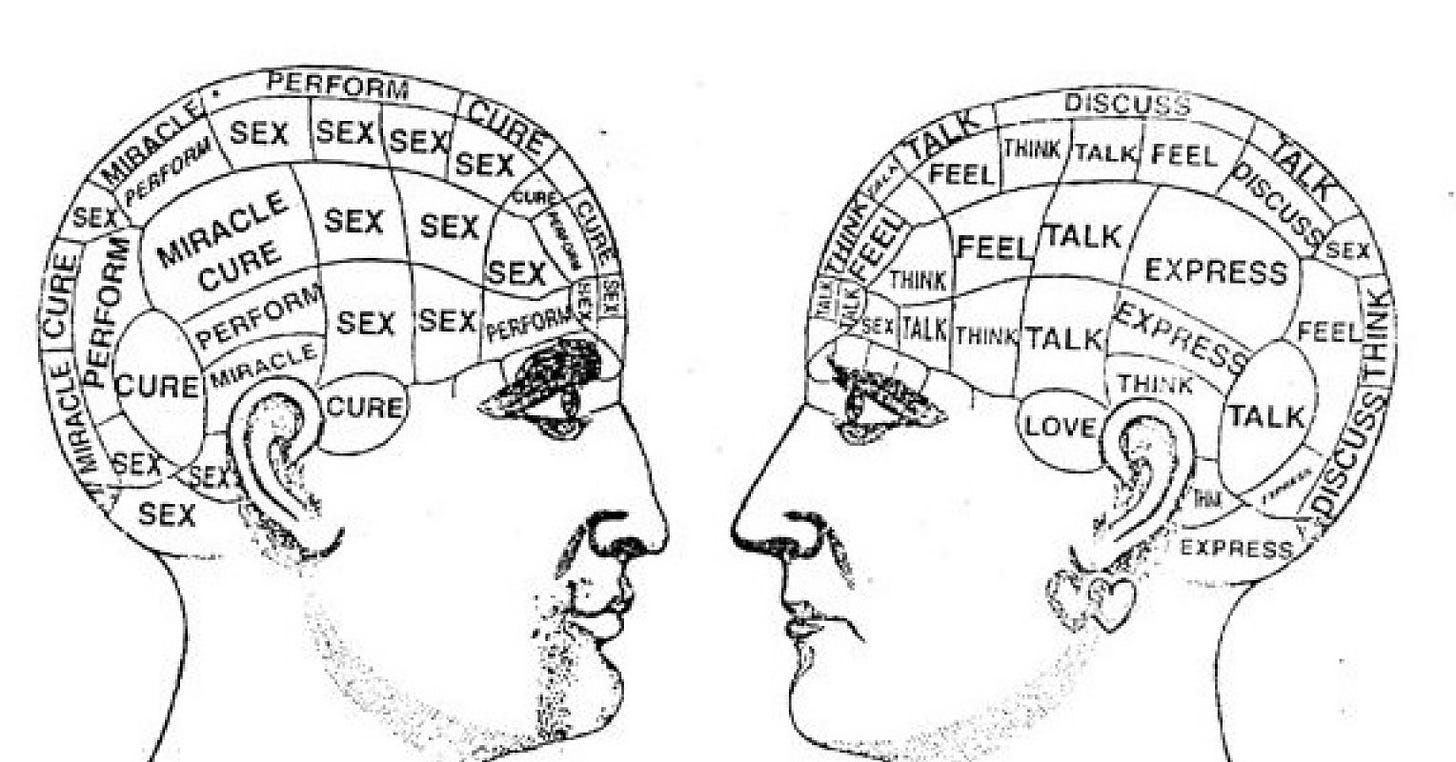

Dr. Kraus: [00:00:33] Well, I think it's much broader than that. And I think birdsong is a nice model because it shares a lot of dimensions with human speech. And we can talk about that, but the whole notion that humans are special? Certainly, from where I stand, it makes very little sense in terms of what we know about the biology of the species, and there are so many commonalities across species. And also... I mean, even back to birds, the way that birds deal with sound, they're actually very interested in not so much the notes but the information that's within each note, those FM sweeps... But they will learn songs, and it's interesting from so many dimensions. On the one hand, there's this sex difference: for the most part it is the male birds that sing and it's the female birds who choose. And so you end up with an auditory system that largely differs in male and female birds and it turns out in some of the work we've done and some of the... Many, many people have looked at sex differences in the processing of sound.

Friar Z: [00:02:20] Yeah, I found that fascinating in the research. Yes.

Dr. Kraus: [00:02:23] And it seems to be hormonally mediated across many, many species.

Friar Z: [00:02:31] But this can also lead to troubles in terms of language acquisition for males, in particular, yes? They are particularly subject to things like dyslexia and so forth. Is that correct?

Dr. Kraus: [00:02:41] Yes, they are. And so as we look at differences between male and female brains, what we see is that the females seem to have stronger responses, especially to the harmonics in sound, and it seems that over time... And I think it is likely to be hormonally mediated because of the work that we have done in animal models, where you can very carefully regulate the hormones and you can see that rats, for example, at different parts of their cycle will process sound differently, as well as just being differences between male and female rats. And the male response is generally weaker, which makes the male more susceptible to disruption.

Friar Z: [00:03:45] Is it weaker, in general, or just certain sound ingredients?

Dr. Kraus: [00:03:48] In certain sound ingredients, certain sound ingredients that are very important for any kind of communication. And we're seeing this also... We're doing a lot of work with athletes, and we're looking at our male and female Division 1 athletes, all 500 of them, and again, we're seeing these sex differences. But when an athlete gets a concussion, it seems as though the males are more susceptible. It's as though the females have some kind of protective element in the way their brains are organized in responding to external stimuli, like sound.

Friar Z: [00:04:39] Wow. Okay, wonderful. Getting into some more kind of technical questions about things, from what we've been talking about. I did mention health effects of sound, the possibilities of therapies for different sorts of things. I mean, you even say in the book that there's the potential for helping with, like, bone fracture healing and this sort of stuff with sound. So, maybe: What are some of the health effects of sound and how does this open up possible therapies for a variety of conditions, maybe other things that you haven't talked about already?

Dr. Kraus: [00:05:19] So, sound is our ally, our friend, and it can be an enemy of brain health and of our sound mind, and I would be remiss if I didn't talk about noise. Because now most people recognize that very, very loud sounds can damage your hearing. But most people don't recognize the health consequences of the moderate level noise that I define as unwanted, unnecessary, unmeaningful sound in our lives. So, again, as an example, there may be a truck outside my window and I won't even know that it's out there and it's running, but at a certain point the driver will turn the ignition off, and you know what happens?

Friar Z: [00:06:21] You notice.

Dr. Kraus: [00:06:23] So, I ask anybody who's listening. Do you ever feel stressed? Do you ever feel anxious? Do you ever have difficulty focusing? Well, it turns out that the sound and the noise that is happening in our lives has an enormous effect on our biological selves, on our physical well-being, on our ability to focus, on our psychological health. Sound is our alarm sense from deep evolution, and we need to be able to remember that sound that I heard that was associated with, "Oh, I almost got killed last time I heard that," or, "This looks like I'm going to have a feast here." You have to remember sound-to-meaning connections. Really, really, really biologically important. And so now we have hijacked this very important alarm system and made it a part of our daily lives, which I think has terrible detrimental effects. And just to get back to your bird songs, our bird songs...

Friar Z: [00:07:47] Oh yeah, talk about that, because that's a fascinating point.

Dr. Kraus: [00:07:50] ... we know that during COVID, many of us thought, oh, now we can hear the birds. Their sounds are... we can hear them over the noise. Well, yes, that is true. But interestingly, it turns out that the birds weren't singing any louder than they were before Covid. They were just singing songs that were much, much more intricate and interesting, you know? I mean, the female bird wants to be impressed by the male who can sing a very intricate and involved song, and so the birds weren't even singing louder. In fact, they were even singing softer because they weren't needing to compete with the din. But as you know, when you make music, if everything is clipping and you have saturated the amplifiers and your brain, you're not hearing the nuances. And so even in birdsong the sounds in our environment very much affect their health and the health of all kinds of of critters in the world, because every critter is really, in one way or another, connected with sound.

Friar Z: [00:09:35] Connected with sound. Yeah. So, noise is a big issue. And that kind of got me thinking: I mean, is it safe to say that there's kind of good sound and bad sound for the brain in some sense in terms of a qualitative aspect? Because what I got a little bit out of the book was that ordered sound, in a way, is more healthy in terms of development rather than disordered sound, as it were. Is there is there anything to that? How would you explain it?

Dr. Kraus: [00:10:05] Well, first of all, I really wouldn't want to make these blanket statements about good and bad sound. You know, everybody always wants a dosage, they all always want... they want it to be binary. And I tell my students and they're so frustrated they want to know the answer. It's always, "It depends." So it depends. But I think that we can safely say that, for example, every time we hear some beep... I mean, does my neighbor need to know every time I open and close my car door? But every time that happens... this is really not necessary. If you're at an airport, an airport already is an inherently noisy place. You can't change the fact that engines are noisy and the conveyor belts make noise and people moving around are going to make noise, but we can change... Every time a boarding pass gets scanned, you can hear it two gates down and people... I think, overall, we want to be making the right choices. We want to do things that make sense, we want to make healthy choices for ourselves and our family. But we aren't aware that something like that which really can be fixed... There's so many things you can't fix, but there are things that we really can fix, which is why it is so important. I keep coming back to choices, to be making... We need to talk to our kids instead of our phones a little more and, you know, things like that.

Friar Z: [00:11:48] What do you see as some of the possible avenues for therapies with sound, then? I had mentioned the bone one, but as I kept thinking through all of this sort of stuff, I started thinking of things like headaches, sleep disorders, stuttering, all sorts of stuff. Are you all looking into that? Is there... Are people talking about this sort of thing?

Dr. Kraus: [00:12:11] We're not specifically looking in those areas. We are looking at -- others are -- we are looking at music as a way to strengthen sound processing in kids who have learning and language problems. We are looking at... So, if you get a head injury and -- we know this from our experience with, with young otherwise healthy athletes -- and it disrupts the synchrony in the brain, and we have some early evidence that rhythm training, actual rhythm training can help not only synchronize the person outside the head, but can synchronize the brain rhythms inside. And this is, you know, one of the areas where we're really trying or seeking funding to get past the preliminary stages and do a huge clinical trial. But that's yet another area. We know already that there's a tight, tight link between music and memory, and we know that people who have memory disorders, even dementia, remember the sounds. They remember sounds that -- especially music, the music -- and we remember... I don't know how many people are now listening to audiobooks. When you read an audiobook, you... Often people say, "I really remember so much more," because you're engaging a different... Think, you're engaging this biologically ancient system, and we've only as a species, we've only been reading for about 3000 years. We've been talking to each other for hundreds of thousands of years, right? So, anyway, memory: even before there was writing, history was brought down, carried down by bards, by the singers. And we remembered the history, we remember our songs, we learn our ABC's through songs. But we also know that a person who is no longer able to recognize their family members, when they listen to a song that has had meaning to them in their life, they're brought back, at least for a time to the world of other people. And this is incredible, and why this isn't a standard of care... I mean, yes, it's increasingly being recognized, but insurance won't pay for it. It's not the kind of care you would typically get.

Friar Z: [00:15:33] Because it's so subtle, you know, it's not a pill. It's something much deeper than that. What it reminded me of was this video I saw a while back of an older woman who had "locked-in syndrome." She had just kind of become locked-in and this sort of thing. And the caregiver was working with her, rocking her back-and-forth and singing to her, and all of a sudden it took like, one, two, three minutes or so, but she came out of it and she started singing along with it. This is a woman who was practically unresponsive to anything else. So, it is getting deep down into our sound minds, as it were, and reawakening ourselves through even just the use of music that way, but also the rocking back-and-forth, I think, the rhythm aspect of it. So, there's proof right there.

Into the Beyond

Friar Z: [00:16:25] Okay. Shifting gears a little bit. So, beyond "Sound Mind," one of the things that I got interested in with this book was running across a small excerpt in it where you had mentioned -- and it's in the book as well -- where you're interested in doing research into this topic of drone, of auditory drone and that sort of thing, and its significance, its applications, what is it doing, and so forth, and I was hoping you could maybe for this latter part of the interview, just talk about what is it that got you interested in it? What are you looking into? What's the plan with all of this stuff for you?

Dr. Kraus: [00:17:01] Oh, man. I am just so interested in this topic and I'm hoping to learn from you.

Friar Z: [00:17:09] Okay. Well, you first, and then I'll add my thoughts.

Dr. Kraus: [00:17:12] Yeah. I really would like to know what you think. Well, first of all, rhythm is... rhythm historically has been a portal to the spiritual.

Friar Z: [00:17:26] Right. And you see that all across different religious traditions? Yep.

Dr. Kraus: [00:17:31] Yes. Did you happen to see "Around the World in 80 Faiths"?

Friar Z: [00:17:36] No, but I'll have to look that up.

Dr. Kraus: [00:17:40] A vicar takes a year off his vicarage in the UK, and goes BBC cameras in tow all over the world. And he wasn't making this point, but what was really obvious to me because of my sound mind is that every single religion has music, of course. And so, there's something about about rhythm. There's something about rhythm. There's something about, well... Rhythm is kind of a key to how biological systems work, in general. You know, there's the basic rhythmicity of cells and within a body of any organism, but the rhythmicity, the back-and-forth, the reciprocity interests me. Do you know... Have you heard of Iain McGilchrist?

Friar Z: [00:18:37] The name sounds familiar, but I don't know where from.

Dr. Kraus: [00:18:40] So he is a physician and a philosopher, a literary scholar, he's written a book called... He wrote a couple of books. One is "The Master and His Emissary," and the other is, "The Matter With Things."

Friar Z: [00:18:59] “The Matter With Things.” Okay.

Dr. Kraus: [00:19:01] But, take a look, if you want a longer take on a subject like this. I had a discussion with him, and it's on YouTube, so if you look for Iain McGilchrist and Nina Kraus it'll come right up. And he has this concept that he calls "betweenness," which to me... He uses it in a much more global manner than I am thinking about it in terms of... This is sound and rhythm, it really embodies betweenness. It's this back-and-forth, it's a reciprocity, it's what happens when I'm singing harmony with you. And it's what happens when you're talking to anyone, when making music with them. It's this back-and-forth, and when you have rhythm and you have vibration, you have this back-and-forth and you have a pattern, and our nervous system relates to itself, it relates to others, it relates to... Who knows the, the...

Friar Z: [00:20:15] Metaphysical realities.

Dr. Kraus: [00:20:17] Yes. I knew you'd help me out here. And so as we try to understand... You know, why is it, how is it, that music is so transcendent in its qualities, in ways that other things just aren't? So if you're a biologist and you want to be able to understand some of these things, you start thinking about rhythm and you start thinking about drones, and you start thinking... So, another person who has had a big influence on on my life is Mickey Hart.

Friar Z: [00:21:11] Right? And he's with the Grateful Dead, one of the guitarists.

Dr. Kraus: [00:21:15] He was a drummer...

Friar Z: [00:21:16] Drummer.

Dr. Kraus: [00:21:18] ... of the Grateful Dead, and importantly, there are two drummers in the Grateful Dead.

Friar Z: [00:21:25] I didn't know that. Okay.

Dr. Kraus: [00:21:26] And so, again, if you think about African drumming, it's polyrhythms. And so, you have... So, when I have interacted with him... And you can look again on our website, and if you look for his name and mine, we've done some shows together. It's called "Say It With Rhythm": it was... We did one, before the pandemic, at the Kennedy Center and he... Well, first of all, there the interaction was with him and with Zakir Hussain, and they were interacting with each other, and I got to interact with them... Again, this reverberation, this reciprocity.

But Mickey Hart has this thing called "The Beam," which is basically a monochord, which apparently Pythagoras really loved this thing, which is these great big fat strings that are tuned in unison. And it's very, very, very much at the essence of the music that you are into, both chorally and metal-ly. Right?

So I've been thinking about this a lot and I would love to... We've done some work with Mickey Hart, he's been over to the lab, and we have taken some of his drone stimuli and have measured rudimentary brain responses. This is something that really takes a lot of time... When you're doing anything that is thorough, it takes time, attention and money. And so, if, again, we were able to have the resources to really study this and the time, this is an area that I think is really ripe to be looking at in the way we are looking at it, which is... You're taking something which is... You have these shamans, running in and out, and drums, and going to life trees and having the drum kind of be the signal to bring them back to the rest of us... And so there's all this stuff going on that is part... I mean, the scientists that I often pal around with are looking at me with cross-eyes because these are things that are very difficult to measure, and yet so many of the important things in life that we care about you can't... You know, how do you measure love? So, but because we are really into signals, I think we can get a handle on this. So, I would really like to be able to do an in-depth study. So, if anybody is listening and wants to be an angel here, and has a deep pocket and wants to fund this work you know, help us out.

Friar Z: [00:24:50] They can get in touch with you through the Brainvolts site?

Dr. Kraus: [00:24:53] Get in touch with me through my email, through the Brainvolts site. I'm very easy to find. And also while I'm talking about this, we at Brainvolts spend way too much time... I mean, right now we are trying to get two NIH grants out the door. All of our work is funded either by the government, by private foundations, and by private philanthropy, because... You should know, I'm a professor at Northwestern University. I'm tenured. My salary is paid. 100% of everything that we do at Brainvolts comes from external sources.

Friar Z: [00:25:41] Wow. Okay. Got it. It's good to know, and so if anybody is interested in supporting this work, this is where to go. Excellent.

What about “drone”?

Dr. Kraus: [00:25:48] So, there's a tremendous amount to be learned from trance, from drumming, and I'm on that road both as a scientist and as a rhythmist. I'm trying to learn something about African drumming and just a way of thinking about multiple rhythms at once. I know a little something about sort of conventional... I'm married to a drummer, we have got three drum kits in the house, so I certainly fool around with that kind of drumming. But it's really different when you have a djembe and you're, you know, in a group and you're trying to be some part of this group. So, you've really... You've come to a sweet spot and one that I think has enormous potential, and I want to hear what you think.

Friar Z: [00:27:03] Yes. My armchair theorizing has been, that there is something about drone, continuous repetition of patterns, all this sort of thing, that auditorily evokes "The Eternal." And that this is something that people... It brings about the response of awe, wonder, something higher, all these sorts of things. And I do think that my... This is my hypothesis: this is why it makes its way into so many different religious traditions of sung music, in particular. So, for instance, if you look at Gregorian chant, there's normally a resting tone around which everything works. Or if you look at organum, which was an early form of medieval polyphony -- which I'm sure you already know about this, but for our listeners sake -- it's a lower droning tone and then variation by another singer over it and this sort of thing, and it's mysterious, it's beautiful, it's all this sort of stuff. And my... Where I got inspired with it is just by noticing, well, I like this aspect in sacred music, but I also really like this aspect in heavy music, heavy modern music. And so this is why, with my own music project, I was like, well, maybe it's doing the same thing for people and they just don't know it. So, my theory with it all was, well, then you should be able to dovetail those two together and they should work together, and in my opinion it does. But again, all of this is based on the theory of... If one is coming from some sort of religious tradition that believes in some sort of transcendent higher-power being, whatever, that there's something audibly about encountering that that is very powerful. And in a way, that might be exactly what people are looking for when they go to a concert, or they go to any sort of other experience that is powerfully... powerful, in terms of the sound experience and that sort of thing. So, this is one of the hypotheses I've had with this music project of my own.

Dr. Kraus: [00:29:15] My scientific gut feeling and everything I know about living as a person tells me you're right. And I am interested as a biologist to understand this better just to get a little bit of... Because I think science has limitations and we need to really acknowledge those limitations. But I do think that we can learn more about...

Friar Z: [00:29:45] Because we're physical creatures and there's something going on here that is embodied.

Dr. Kraus: [00:29:50] Exactly. Yeah.

Friar Z: [00:29:53] So, that's my interest in it. And so I very much look forward to the results of your research down the line. And I will certainly be advertising your work, because I want to see what you come up with in terms of your own research. Good. Just a few last quick questions. You know, one of the things that I was wondering about is, you know, we talk about language acquisition and all this sort of stuff and the practice of language and that sort of thing. But then I was thinking of it... I'm like, well, yeah, but what about those religious communities that are highly cloistered and highly silent, you know? Like you watch this film, "Into Great Silence" with the Carthusian monks and this sort of thing... Now, admittedly, they are regularly participating in liturgy every day, and so they're chanting the Psalms, they're doing all these sorts of things, but most of the time they're just silent. So, is that good? Is it healthy? What's going on in their heads in terms of their thought? Right? Because this is such an embodied reality. So, anyways, that was just one of the questions I had, and it would be interesting to look at how they process sound and comparison with people who don't live that sort of life. And what do you see in terms of the sound component? Sound ingredient responses and stuff like that? So that's one thing that I came up with as a future research thing.

Dr. Kraus: [00:31:09] You should be the scientist. But I think an important point is that they are probably hearing a lot more than we are, because there are so many sounds... There are so many sounds that we are unable to hear because of our noisy world. There are so many sounds that we are unable to hear because we just haven't quieted our minds and our bodies. So, it would not surprise me at all if they were in fact intently listening to certainly birds and insects...

Friar Z: [00:31:47] That they notice things we don't about their own environment.

Dr. Kraus: [00:31:50] ... how we breathe, how we... The sounds of people chanting, breathing together there... I think that "quiet" is not the absence of sound, and it would not surprise me at all if these people living cloistered lives sonically have some of the richest...

Friar Z: [00:32:20] Experiences of the world, sound-wise.

Dr. Kraus: [00:32:22] ... "sound minds."

Friar Z: [00:32:23] Yeah, absolutely. Yeah.

Dr. Kraus: [00:32:25] You know, again, I don't know. We gotta do the experiment.

Friar Z: [00:32:27] That's cool. Excellent. What about if a person is deaf? How does that affect things?

Dr. Kraus: [00:32:35] Such a good question. So, I'm working on this now, here's another thing. Again, if I can have time and money...

Friar Z: [00:32:42] Oh, of course, of course.

Dr. Kraus: [00:32:43] ... I'm working on another book, and this one's all about music. And one of the things that really fascinates me because of my line of work is, I have met so many people who are deaf, have cochlear implants, have hearing aids, and yet their interaction with music is wonderful and profound.

Friar Z: [00:33:08] Wow. Okay.

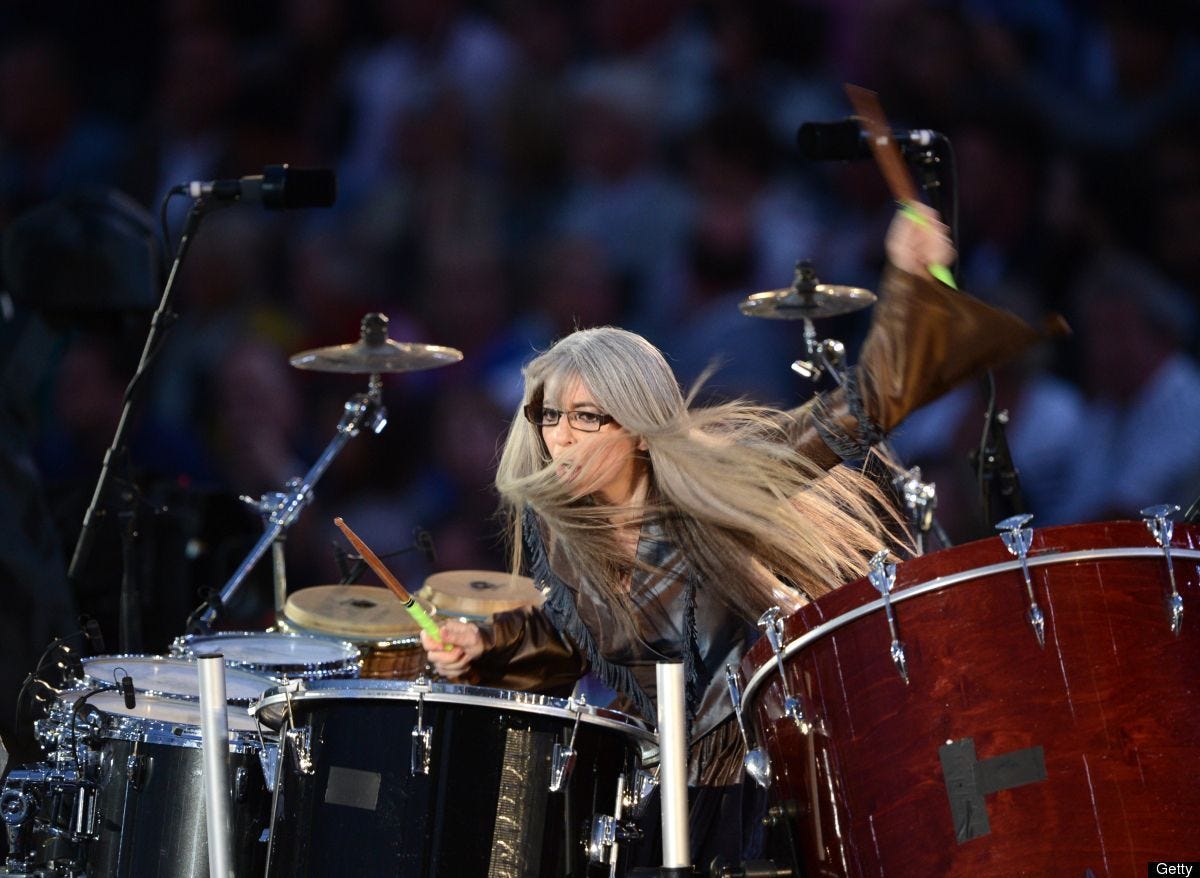

Dr. Kraus: [00:33:09] And music is... I mean, think of, you know, Evelyn Glennie?

Friar Z: [00:33:13] No, I don't.

Dr. Kraus: [00:33:14] She's a deaf percussionist.

Friar Z: [00:33:16] Okay.

Dr. Kraus: [00:33:16] And you know... And again, there's so much of sound and so much of the world that we, that many of us aren't tuned to listen to, but we can if we learn to... It's another form of, one form of vibration or another.

Friar Z: [00:33:32] Well, and I think you make the point in the book that when one sense is more disabled, there are other aspects of ourself which are capable of compensating as well.

Dr. Kraus: [00:33:44] Absolutely.

Friar Z: [00:33:45] And so this makes other things possible, even like, for instance... I think you bring out the point even those who have autism, for instance, can show highly creative lives in other various different ways that just wouldn't be possible otherwise, for instance.

Dr. Kraus: [00:34:00] Yes. But you know, I am of the mind that -- and this is just not conventionally the word on the street -- given what we know about how sound and making sound-to-meaning connections strengthens the hearing brain, if you are losing your hearing, why wouldn't you use music as a way to strengthen your sound mind? And the fact is, I know musicians, I know many people... I mean, this is possible, and I've been quite intrigued... On the one hand, as a scientist I work with big data, and what we can learn from large populations and many, many data points that give us statistical rigor. And, on the other hand, because of my lab and people come to us, I have been able to get to know and to interview individual people who show us not what's typical but what's possible. And what I am really learning loud and clear... These people who, in fact, have various forms of deafness, are saying that music is a way of strengthening sound processing in the brain and strengthening all kinds of communication with the world.

Friar Z: [00:36:00] So, music is still the key with a lot of this stuff. That's wonderful. Last quick question for you. This phenomenon of creativity is something that I just... It's so philosophically rich and one can look into it in a variety of ways, and it hit me again reading this book... Again getting back to the songbirds, right? There's... They learn songs and this sort of thing, but they're fairly fixed. There's something about the human being that is able to take sound and rework it in a seemingly infinite number of ways, right? What is it biologically that's going on inside of us that makes this sort of thing possible? Do you have any insight into that?

Dr. Kraus: [00:36:48] Not really, except that... And, you know, first of all, I think people who have really studied birds and bird songs, yes, they are, they can be quite ritualized. But there is way more improvisation...

Friar Z: [00:37:08] Yeah, some are more flexible. I think it was canaries, weren't they, for instance?

Dr. Kraus: [00:37:13] Yeah, and also it's a matter of being nuanced in the listening, you know? I mean, we often don't know what to listen for in another language.

Friar Z: [00:37:24] Right.

Dr. Kraus: [00:37:26] But with respect to creativity... And I think about this again as a musician. So, on the one hand, there are rudiments that you have to learn and you practice and you learn all kinds of detail as a musician. And it takes hard work and there's repetition... Again, it's a rhythm: it's repetition, repetition, you do it again and again and again, you practice a lot, you play a lot, you learn many, many different skills. And then at least for me, when I'm improvising I'm not really thinking about what I'm doing. I'm clearly drawing...

Friar Z: [00:38:14] On experience.

Dr. Kraus: [00:38:15] ... on experience. And so, again, I think that experience, and our sonic experience is so important. And your listeners, actually... It's funny, we were talking about Mickey Hart and his beam. I have something called the "BEAMS Hypothesis" you can download, it's an article that I wrote for a journal called "Hearing Research."

Friar Z: [00:38:39] Okay. "BEAMS Hypothesis."

Dr. Kraus: [00:38:41] It's only 400 words long.

Friar Z: [00:38:43] Okay. That's an easy read.

Dr. Kraus: [00:38:45] But I talk about efferent and afferent, and I wish I would have come up with the "BEAMS Hypothesis" when I wrote "Of Sound Mind"... It sort of gelled afterwards. But the idea of experience and how we learn and we practice, and why the old men are the best drummers? We just do things again and again and again and then draw upon them in our daily life. And I would expect that we draw on them when we are coming up with some...

Friar Z: [00:39:24] New things.

Dr. Kraus: [00:39:24] ... some new thing, right?

Friar Z: [00:39:26] Yeah, basically. I mean, this all makes sense from... As a member of my religious order, the Order of Preachers, also known as the Dominicans, we love Aristotle, and Aristotle really talked a lot about habituation, and that one is shaped by everything that comes through the senses and this sort of thing, right? And not just individualistically, but also in combination, and that this is really what we're working with inside of ourselves when we're able to imagine. That I can think of a unicorn because I know what a horn is and I know what a horse is, and I can synthesize all that stuff, you know? And all of this is just kind of getting back to these fundamental insights that even people going back 2500 years ago were able to reach about what is going on inside of us in terms of this creativity. Well, it has to be based in experience and then mysterious inspiration, perhaps, from that. But really, you don't know until you've really experienced it yourself in a way. So, I just think that's a beautiful aspect of creativity, and everything that you're saying, especially based on your research, is just wonderful affirmation of all of that. So, yeah.

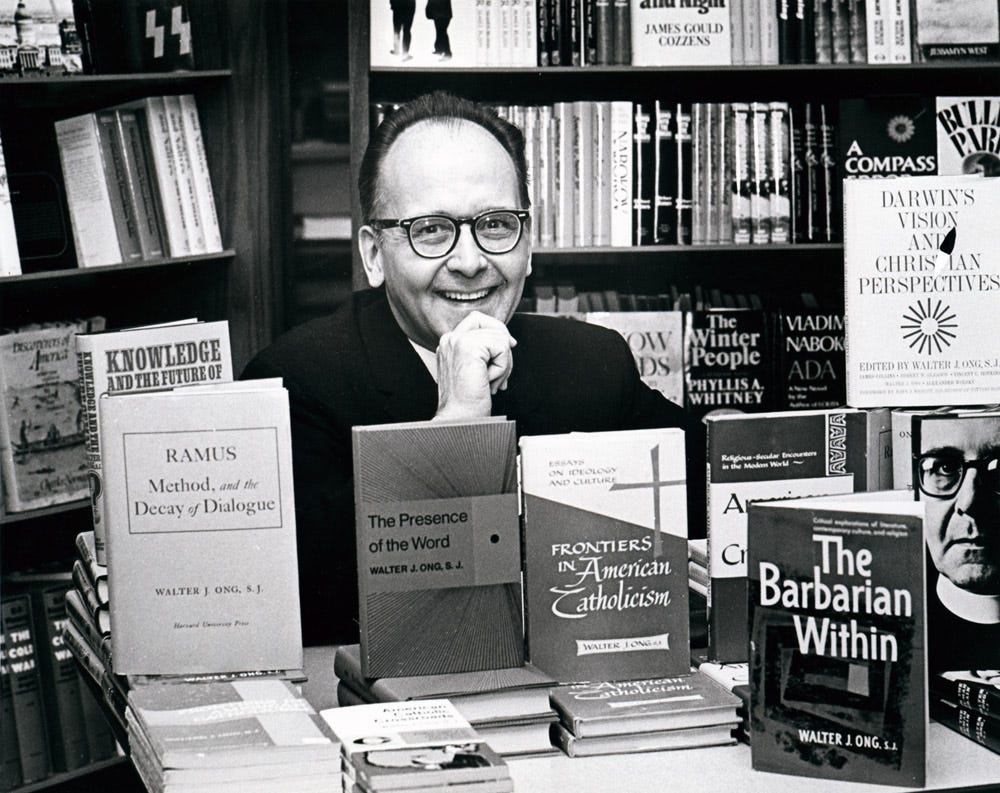

Dr. Kraus: [00:40:35] Do you know the work of Walter Ong?

Friar Z: [00:40:37] Yes, I am aware of it. Yeah, he was at Saint Louis University.

Dr. Kraus: [00:40:42] There's a book that is all about sound, and he really brings it back to the word. [Probably: “Orality and Literacy"]

Friar Z: [00:40:47] Great. I will have to go and look back into him again. One of our brothers back in Saint Louis is very interested in him because of his communications background. So, yeah. Okay, I'll have to look in that direction next, so thank you. Well, it's so good to talk with you, Dr. Kraus, today about all of your research, and I thank you for writing this book and for the work that you're doing. I love sound, and it's great to just read this book and really sort of capture a new sort of understanding of it all. So, just wish you the best in all of your research. We'll definitely be posting links to your website and recommending funding what you're doing. And I certainly look forward to the years to come of what it is that you and your team have to produce from your wonderful Brainvolts lab into the future. So, thank you for being with me today to talk.

Dr. Kraus: [00:41:36] Thank you. But thank you for the creative work that you are doing, pulling together this liturgical singing and metal...

Friar Z: [00:41:52] I call it "sacracore."

Dr. Kraus: [00:41:59] ... it's wonderful.

Friar Z: [00:42:02] Yeah. Thank you for that. Wonderful. So, I look forward to your work and you look forward to mine. And I guess we'll maybe talk in the future even.

FIN.

I hope you found these interviews interesting! Please subscribe, and head over to the ÆTERNUM website to check out its releases and to learn how you can support its work.

Share this post