After a (too) long hiatus, we finish-up the second of the two-parter (begun with the previous post) describing a genealogy of sorts for the ÆTERNUM project. It’s worth describing this genealogy in order to contextualize the project’s most “first fruits”: “Domine refugium.” Once again, I cannot promise a comprehensive genealogy of all the ideas ÆTERNUM synthesizes into its music, but if you have opinions about our “family tree” please contact us here.

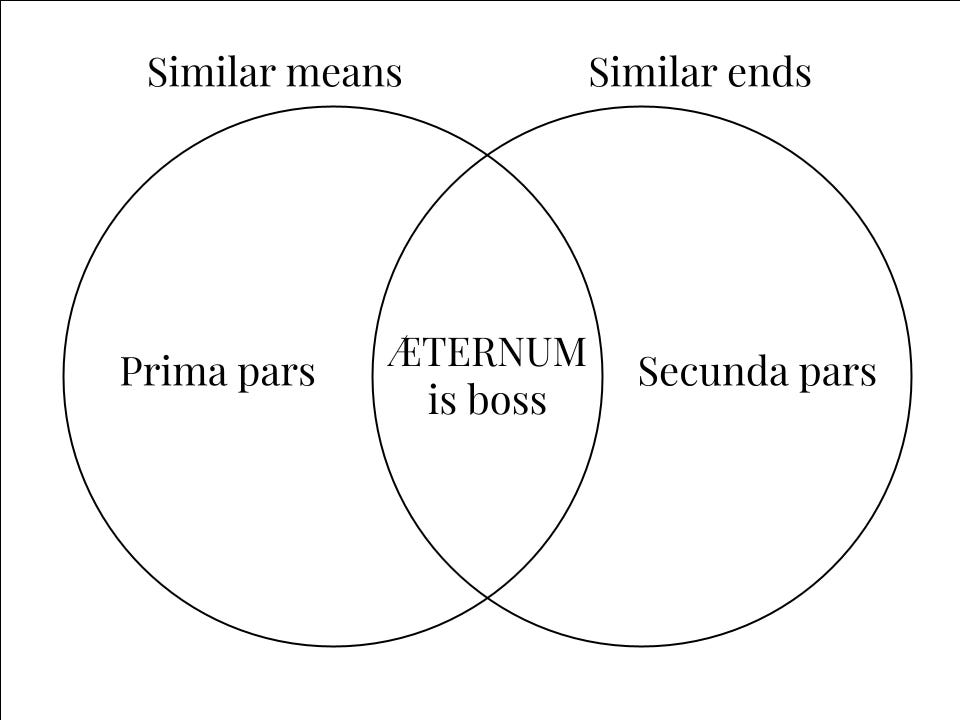

Thus, we continue considering precursors to ÆTERNUM: the previous post dealt with musical projects that used “similar means”; this one will consider those that had “similar ends.” In visual form once more…

This “second part” likewise cannot claim to be comprehensive, so we limit ourselves to a few touchstones…

Secular Groups, Religious Themes

(I cannot claim any knowledge of these persons’ actual religious commitments. I’m only going on intuition given what I’ve seen and heard.)

Jesu

One of my all-time favorite artists is Justin K. Broadrick. Not well-known in popular music scenes, he is legendary for his pioneering work in industrial metal in the late 80’s and early 90’s before it was appropriated and commodified by major record labels.1

Many of these groups were obsessed with religious themes, as reflected in their band names: Nine Inch Nails, Ministry, etc. Characteristic of their music was the use of drum machines, abrasive guitars, and shouted (often distorted) vocals. Now almost none of these groups were respectful of religious belief. But the best ones nevertheless authentically brooded over existential issues that are the common heritage of the human race, illuminating the experience of “being alienated from the good” (what Christians identify as “sin”) and lamenting it, not glorifying it. This is different from other musical acts that revel in “alienation from the good” as such, embracing it as an identity of sorts. The latter find satisfaction in the darkness, while the former seem to have some openness to the possibility of the light… maybe even a yearning.

My familiarity with JKB began with his band “Godflesh” (religious-themed name!) during my early college years when I was more into “noise rock” (e.g. Sonic Youth) than metal. Godflesh’s similarity of ethos to an earlier pioneering group, Big Black, got me immediately interested. I enjoyed some Godflesh tracks but not everything: the lyrics were too much oriented towards darkness as such.

But then a friend introduced me to a more recent project of JKB — Jesu — with a copy of its EP, Silver. I was completely blown-away: never had it occurred to me that you could combine metal instrumentation with shoegazer song elements, and all with the use of drum-machines (typically).2 The eponymous track really sets the tone: an aloof meditation on aging (apparently), sung not shouted, with heavy guitars, yes, but also with arpeggiated guitars, piano, synths, etc.

And what’s with that band name, “Jesu”? After a quick web search, I managed to dig-up a 2008 interview with JKB that I read long ago, done by some random German dude with a “Blogspot” (remember that?). You can read the whole interview here. It’s a fascinating look into JKB’s inspiration for the Jesu project. These portions are particularly illuminating:

R.: Godflesh and Jesu are both names that carry a spiritual or religious meaning with them. Are you a spiritual person?

J.B.: I’m totally a spiritual person. I’m absolutely obsessed with any form of spirituality. […] I’ve always been obsessed with everything esoteric and everything to do with spiritual cultism. All these things absolutely fascinate me. Belief systems are really fascinating. It was the same thing with Godflesh. It’s all questions, you know? Jesu is all questions and Godflesh is all questions. I’m not smart enough to have answers. I’m the same questioning person that we all are. For me everything is a question. I think I’m on the same stupid or cheesy spiritual quest that a lot of people are in but without the need of any form of dictated religion. Obviously we’re totally anti organized religion. When I say anti organized religion Satanism is pretty much in the same bracket. But religious iconography is something I’m really obsessed with. The imagery of religion, the feeling of like when you walk into a cathedral, the huge feeling of intimidation that you get from Christian religion – everything to do with religion I find totally obsessive.

R.: So is it more the atmosphere of spirituality that you want to carry in the music?

J.B.: To some extent, yes. I think it’s trying to create a similar spiritual feeling. The closest I can ever get to any form of God is through art. So it’s either music or great books or great films. But for me music… and films I think… it’s close but music for me is ultimately the thing where I personally can get emotions that I can’t even articulate. They’re illiterate emotions. With Jesu we’re definitely trying to create music which evokes that same atmosphere where the peaks of the emotion is so intense that you can’t really put your finger on exactly what it is. Those are moments in music I really enjoy. It’s like a blind emotion – absolutely inarticulate, illiterate, where words have no meaning anymore. Religion obviously evokes the same feeling of belief in people where it’s like a blind belief. It’s fascinating that people can just put their whole body and soul into something… But I can see this in myself. I can see how it is possible to be absolutely absorbed by feelings of pure love or pure faith. It’s something I’m really intrigued by. I’m intrigued by what’s beyond this shit… what’s past the skin and past the mind and everything.

If I had to present someone with a textbook example of a yearning for God expressed in innocent, apophatic language, I’d be hard-pressed to find a better example than the above. Whether JKB would ever become a committed Christian3 is beside the point: he pays attention, he can verbalize the right metaphysical questions, he understands the place of the emotions and art in religious belief, and so on. When I first read this, I found it heartening, particularly because I was listening to Jesu during a period of my life when I was returning to the practice of Christian faith. “If JKB can be inspired by religious belief, then why not me?”

Many of the works from Jesu are worth considering. The last one I’d like to draw attention to is JKB’s rework of the title track from its Christmas EP, released in 2018 for performance during some weirdo fashion show, of all things.

Sheesh, JKB: more like “Life Teen Mass”! Astonishingly beautiful, the song’s lyrics consist of single words for each verse: Life, Mass, Tears, Gold, and so on. When I listen to the song, I think: “Nativity scene.” Totally epic.

Om

This was the teaser I left you with last time…

Al Cisneros is an interesting dude. He is best known for his early work as bassist for the stoner-metal band Sleep. With lyrics celebrating (and inspired by) the smoking of Mary Jane, the band’s albums and songs consistently reference Jewish religious themes: a track over here titled “Nebuchadnezzar's Dream,” an album over here titled Holy Mountain that includes a song titled “Nain's Baptism,” an album right in front of you titled Jerusalem, and so on. Actually, that last example was a shortened version of their epic Dopesmoker album that consists of a single hour-long track, recorded in three parts only due to the technical limitations of multi-track recording lengths. The lyrics are completely absurd, a mash-up of Jewish pilgrimage and stoner culture.

Is it irreverent? I’m actually not sure. It’s not mockery: it’s like a religious interpretation of stoner culture using the Judeo-Christian language that Cisneros and company were probably raised in the midst of. And it’s not inconsistent with one of Sleep’s major inspirations, namely Black Sabbath, whose album Master of Reality is a major touchstone for any explicitly Christian metal group.4 As Wikipedia notes of Black Sabbath, “Butler, the band's primary lyricist, had a Catholic upbringing, and the song ‘After Forever’ focuses entirely on Christian themes” — though this single mention of the Christian themes of the album comes only after an extensive discussion of marijuana on the composition of the album: you can see where the editors’ interests lie. Whatever. Even Ozzy Osbourne himself seems to have long been a member of the Church of England, praying before each show. Substance abuse problems and shocking behavior? You betcha, but sinners all are we! If you need a better role model, go with Alice Cooper.

But my purpose is not to talk about Sleep… well, except to mention one last thing. The earliest incarnation of Sleep included guitarist Justin Marler, who left the band… to become an Eastern Orthodox monk in Alaska! From there, he founded the “zine” Death to the World, dedicated to evangelizing rock music culture by presenting Christianity as “The Last True Rebellion.” The ‘zine continues in online format today, offering a nice overview of its history and purposes.

BUT MY PURPOSE IS NOT TO TALK ABOUT SLEEP. Rather, I wanted to talk about another project of Cisneros, Om. The Wikipedia page says it all:

Om's works incorporate musical structures similar to Tibetan, Byzantine and Ethiopian chanting… The band's name itself derives from the Hindu concept of Om, which refers to the natural vibration of the universe. Every album from Pilgrimage onward features Eastern Orthodox iconography in the cover art.

One of Om’s best songs is “State of Non-Return,” found on their Advaitic Songs album, which also features the songs “Gethsemane” and “Sinai,” and sports a cover featuring an icon of St. John the Baptist in a position of humility before God.

Now, I know it’s all syncretistic: Cisneros is mixing all manner of “Eastern” influences both musically and lyrically. But none of this seems insincere: like Justin K. Broadrick, he seems like one who is pondering over deeper existential and metaphysical questions. And I appreciate this, not the least because the music is often quite beautiful, but more so because he seems to take religious thought and yearnings seriously.

In both cases, Jesu and Om, we find artists composing music that is radically opposed to cultural currents that are either aggressively indifferent (“religion doesn’t matter”) or actively hostile (“religion is a threat”). I’m willing to regard any artist as a fellow-traveler of sorts who can at least appreciate the appeal of human religious yearnings instead of merely writing them off as an accidental product of evolutionary forces or whatever that must be snuffed-out for the sake of “progress.” For this same reason, I love products of science fiction culture like the novel Dune or the TV show Star Trek: Deep Space Nine.

So, I offer these artists as just two examples of many who, though perhaps uncommitted to a particular tradition of religious belief, nevertheless infuse their music with religious themes and thereby expose their (secular!) audiences to the same for consideration.

Religious Groups, Secular Audiences

While there can be “secular groups” whose music incorporates religious themes, thereby avoiding easy “siloing” into anti-religious music categories, there are also explicitly “religious groups” who want to appeal to secular audiences rather than be siloed within various “Christian music” scenes. Examples of the latter are numerous, so I limit discussion to only a few that have made the most impact on me.

Scaterd Few

I mentioned Scaterd Few in my very first post, but they are worth going over in greater detail.

I encountered this group during my noisy college years during a stage when I was at least open to listening to weird Christian groups. Their greatest achievement is also their earliest album, Sin Disease. The album is a Scripture-saturated romp through topics of the day: personal conversion, gang violence, drug usage, apocalyptic hope, and so on. It’s also more than just straight punk music. SF developed during a period of the LA music scene when groups like Jane’s Addiction, Red Hot Chili Peppers, et al. were integrating hardcore with metal, rap, prog, dub, reggae, and funk, creating musically dense (and sometimes very weird) music. I mean, listen to this…

The whole album is worth listening to, incorporating jazz and dub elements and such. But what I find most compelling about this group is their ethic: they deliberately sought to play in secular venues to secular audiences, not limiting themselves to the “Christian rock” circuit. Rather, they believed their music rocked sufficiently to appeal to audiences of any background. Here’s the same clip of them playing the song above in 1990 at “The Cattle Club,” a venue that hosted the likes of Nirvana and Green Day at various points:

Danielson

During the same period when I tripped across Scaterd Few, a friend introduced me to the even weirder Danielson Familie.

This friend gave me a copy of their then-most recent album Fetch the Compass Kids… and at first I hated it. Above all, I couldn’t stand the ridiculous vocals of Daniel Smith, but as I kept listening to the album I gradually became captivated by the complexity of the music and Smith’s often surreal lyrics. I couldn’t help but laugh also at the self-made uniforms they would perform in, all of them normally featuring a heart patch on the arm. Here’s a sample:

The instrumentation is all over the place: violin, piano, xylophone, guitars, synthesizer, and who knows what else. The lyrics are a critique of self-absorption and the modern obsession with the high-efficiency rat-race that’s only gotten worse since then. Most of Smith’s lyrics are all about resisting the dehumanizing tendencies of modern society, finding one’s dignity in being a child of God (hence “Daniel-Son”).

Danielson is another example of a “band of Christians” (not a “Christian band”) who deliberately sought to play in secular venues for secular audiences. The album I mentioned above was even recorded by Steve Albini, the infamous head of the industrial noise rock act Big Black I mentioned earlier. By far my favorite album by them is Ships, a good opportunity to show what they were like performing live during the period after it was released:

Danielson became so notable that someone even made a documentary about their origins and ethos. It’s worth checking out, along with another documentary on which they appear, the aptly titled “Why Should The Devil Have All The Good Music?” Unfortunately, all of this seems to be pretty dead as of 2024. We’ll see where things go in the future.

Fratello Metallo

I must mention this example in closing, ashamed to admit that I didn’t know about this guy before starting ÆTERNUM: Fr. Cesare Bonizzi, OFMCap, mistakenly (but appropriately) known as “Fratello Metallo.”

Yes, that’s right: the Capuchin Franciscans in Italy beat us to it. The full transformation of Fr. Bonizzi into a metal star apparently came with his 2008 album, Fratello Metallo,and it made quite a splash. He and his band played at Italian metal festivals, like “Gods of Metal” and this one in 2009:

His music is pretty good, actually, and I have no doubt that he made a few converts… especially in the mosh pit. But things didn’t last very long. Fr. Bonizzi, like any humble priest, knew when to call it quits. The Wikipedia article has this great quote, describing his reasons for stopping things when he did:

The devil has separated me from my managers, risked making me break up with my band colleagues and also risked making me break up with my fellow monks. He lifted me up to the point where I become a celebrity and now I want to kill him.

Pride is the deadliest weapon of The Enemy, and Fr. Bonizzi was Holy-Spiritual enough to know when that weapon was being wielded.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the music projects reviewed in this post all share a “similarity of ends”: integrating “spiritual” themes (more or less Christian) into their music while appealing to secular audiences. The close of the “argument” begun in the first article is that ÆTERNUM is trying to fit into a sweet spot that combines the “similarity of means” with the “similarity of ends” documented in these various precursors, thus making it worth attempting even if only for the sake of innovation.

But I also wanted to write this two-part series of articles for personal reasons. All of the groups discussed have been important in my life during the last 15 years as a demonstration that I wasn’t alone: there are people like me who love to listen to and make noisy, beautiful music while working through deep existential issues and embracing spiritual yearning. I credit these artists with being providential instruments of God that taught me: (A) that it’s “cool” to think about these things and even to commit to them; and (B) that you don’t have to reject everything you like in order to be a sincere, believing disciple of Christ. Rather, we can find beauty and good in a lot of things… though prudence, of course, dictates a certain “sifting” and discernment when it comes to what one enjoys for the greater glory of God.

I hope this has been an enjoyable and fascinating read for you all. Please pray for the project and support ÆTERNUM’s work by either donating to its future endeavors or becoming a paid subscriber to this newsletter.

Stay tuned especially for something special: a podcast interview with Dr. Nina Kraus about her book Of Sound Mind.

Peace upon people of good will,

Friar Z

Similar to how Nirvana prompted the capitalization of alternative rock, thus destroying it, the group probably most responsible for this development in industrial metal was Nine Inch Nails. Every radio-played group of this sort sounds like a knock-off of NIN. Boring!

Then again, it was around this same time that I encountered a group named Nadja, whose first album, Truth Becomes Death, has an opening track that is 23 minutes (!), and that is both stunningly beautiful and terrifyingly heavy.

JKB claims to be “anti organized religion” in the interview. I might joke with him: You’ll never find a more disorganized religion than Catholic Christianity, LOL! Bp. Barron recounts in his “Letter to a Suffering Church”: “The Emperor Napoleon is said to have confronted Cardinal Consalvi… saying that he, Napoleon, would destroy the Church—to which the Cardinal deftly responded, ‘Oh my little man, you think you’re going to succeed in accomplishing what centuries of priests and bishops have tried and failed to do?’ In a similar vein, the early twentieth-century Catholic writer Hilaire Belloc made this rather acid observation in reference to the moral and intellectual quality of the Church’s leadership: ‘The Catholic Church is an institution I am bound to hold divine—but for unbelievers a proof of its divinity might be found in the fact that no merely human institution conducted with such knavish imbecility would have lasted a fortnight.’”

Note the opening track, “Sweet Leaf,” BTW.